Sunday, November 1, 2015

Black Cubans Experience a Different Kind of Discrimination Edited by: Joshua Lim

|

| An Afro-Cuban dance troupe performs in Havana, Cuba, at the beginning of 2014. (via Wikipedia Commons) |

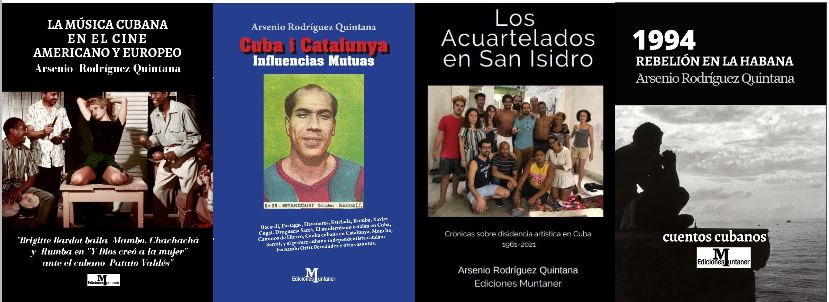

When Arsenio Rodríguez Quintana walked down the streets of Havana, Cuba — where he lived for much of his life — with his then-spouse, police officers would often stop him.

He said they would accuse him, a black Cuban, of trying to rob the light-skinned woman next to him.

Though the island nation of 11 million is a melting pot of ethnicities, dark-skinned residents have been barred from some opportunities their lighter-skinned neighbors are afforded, as seen in the mostly white government.

He said they would accuse him, a black Cuban, of trying to rob the light-skinned woman next to him.

Though the island nation of 11 million is a melting pot of ethnicities, dark-skinned residents have been barred from some opportunities their lighter-skinned neighbors are afforded, as seen in the mostly white government.

It is racism, Rodríguez said bluntly in Spanish during a video interview, but it is a different type than what blacks experience in countries like the United States.He said communities are more segregated than in Cuba.

“It is universal,” Rodríguez said. “But no one can imagine the racism in Cuba.”

Racism in Cuba

More than one-fifth of the Cuban population identifies as mestizo, and about half as many consider themselves to be black, a 2012 survey of the country’s demographics showed. Nearly three-quarters of U.S. citizens identify as white, according to the 2010 census. About 13 percent identify as black.

Frank Calzon, executive director of the Center for a Free Cuba, a human rights group based in New York, said it is hard to explain to Cubans that the U.S. has a black president.

“The Cuban government denies, it’s in denial that they have a race problem in Cuba, and they do have a serious race problem,” Calzon said.

Fidel Castro declared that the Cuban Revolution of the 1950s would put an end to racism in Cuba.

It is common to see mulattos with green eyes and smooth hair, and blacks with narrowly shaped eyes in the same Havana neighborhoods, according to Juan Carlos Zabala Pico, a doctor from Ecuador who has lived in the country for 11 years.

Zabala said they have a saying in Cuba, “El que no tiene de Congo tiene de Carabali,” which means “He who does not have Congolese in him has a mix of all the other races.”

“It is easy for an immigrant to communicate with someone in the country,” Rodríguez said. It just requires using indirect means, such as emailing his blog posts to people, as opposed to them reading it on the site.

Rodríguez said that despite racial tensions in Cuba, “the mix (of ethnicities) is normal.”

But so is the racism, he added.

Zabala recalled a time when he saw a black 15-year-old running from a white teenager who was throwing rocks at him in the streets of Havana. The 30-year-old orthopedic surgeon, who worked at the hospital Calixto Garcia de la Habana, said similar incidents are common.

Calzon said inequality is felt more subtly as well.

“If your skin is very, very black, your chances of getting a job at a front desk or something at a hotel, your chances are very limited,” Calzon said.

When asked about his own ethnicity, Calzon was quick to answer.

“To be a Cuban is to be an Afro-Cuban,” he said. “We eat the black beans the slaves brought from Africa.”

“It is universal,” Rodríguez said. “But no one can imagine the racism in Cuba.”

Racism in Cuba

More than one-fifth of the Cuban population identifies as mestizo, and about half as many consider themselves to be black, a 2012 survey of the country’s demographics showed. Nearly three-quarters of U.S. citizens identify as white, according to the 2010 census. About 13 percent identify as black.

Frank Calzon, executive director of the Center for a Free Cuba, a human rights group based in New York, said it is hard to explain to Cubans that the U.S. has a black president.

“The Cuban government denies, it’s in denial that they have a race problem in Cuba, and they do have a serious race problem,” Calzon said.

Fidel Castro declared that the Cuban Revolution of the 1950s would put an end to racism in Cuba.

It is common to see mulattos with green eyes and smooth hair, and blacks with narrowly shaped eyes in the same Havana neighborhoods, according to Juan Carlos Zabala Pico, a doctor from Ecuador who has lived in the country for 11 years.

Zabala said they have a saying in Cuba, “El que no tiene de Congo tiene de Carabali,” which means “He who does not have Congolese in him has a mix of all the other races.”

Foreigners, such as Limam Boicha, who moved to Cuba in the early 1980s from Western Sahara, contribute to the cultural mix found on the island, as well. However, Boicha, who lived in Cuba for nearly 13 years, said he never experienced racism.

“In Cuba, I never felt like a foreigner, and the people never discriminate against you for the color of your skin, nor for being a foreigner, on the contrary they treat you well, very well,” Boicha said.

Cultural integration in Cuba

Blacks brought from Africa to Cuba as slaves were able to maintain parts of their culture, including languages, religion, music and dances. As a result, African traditions can be heard in Cuban music, tasted in the food and seen in the street performances in the island’s cities, Rodríguez said.

Compared to black slaves’ experiences in the U.S., Cuban blacks were given more freedom to retain their traditional cultures, Rodríguez said.

Rayko Ferrer Iglesias said that “mezcla,” which means mix, of ethnicities in Cuba has morphed into what is now known as the Afro-Cuban culture.

Ferrer is a dance professor from Cuba, who teaches Afro-Cuban culture mainly through art, on the island of Dominica. He said in an email that Afro-Cuban folklore has become synonymous with Cuban arts. Arguably, the most evident examples are heard in the rhythms of Cuban music.

“In Cuba, I never felt like a foreigner, and the people never discriminate against you for the color of your skin, nor for being a foreigner, on the contrary they treat you well, very well,” Boicha said.

Cultural integration in Cuba

Blacks brought from Africa to Cuba as slaves were able to maintain parts of their culture, including languages, religion, music and dances. As a result, African traditions can be heard in Cuban music, tasted in the food and seen in the street performances in the island’s cities, Rodríguez said.

Compared to black slaves’ experiences in the U.S., Cuban blacks were given more freedom to retain their traditional cultures, Rodríguez said.

Rayko Ferrer Iglesias said that “mezcla,” which means mix, of ethnicities in Cuba has morphed into what is now known as the Afro-Cuban culture.

Ferrer is a dance professor from Cuba, who teaches Afro-Cuban culture mainly through art, on the island of Dominica. He said in an email that Afro-Cuban folklore has become synonymous with Cuban arts. Arguably, the most evident examples are heard in the rhythms of Cuban music.

|

| Santeria is a system of beliefs that merge the Yoruba religion with the Roma Catholic and Native Indian traditions. (via Jorge Royan) |

“Any Cuban that tells you that we are not integrated would be lying,” Ferrer said. He added that traditional African dress can be seen in the countryside, and many medicines are rooted in African “recipes.”

Many of Cuba’s religions has its roots in Africa. Malcom Alomia Quieñones, a Columbian doctor who studied and lived in Cuba for nine years but recently moved back to Columbia, practices the African religion of Yoruba. In Cuba, it has been integrated into Santería, a religion based in multiple African beliefs.

Many of Cuba’s religions has its roots in Africa. Malcom Alomia Quieñones, a Columbian doctor who studied and lived in Cuba for nine years but recently moved back to Columbia, practices the African religion of Yoruba. In Cuba, it has been integrated into Santería, a religion based in multiple African beliefs.

“It is frequent that a person practices two or three religions,” Alomia said.

Various organizations exist in Cuba that aim to educate about African traditions, said Lazaro G. Guevara Lopez, a Cuban writer. But they do not necessarily tell the most authentic history of blacks on the island, he said.

So Guevara and Rodríguez have started multiple groups, such as the Foundation African American of Cuba, promoting equality in the country. They are only given that freedom, however, because they now live in Barcelona, Spain.

Rodríguez said it costs about $5 to use the Internet for an hour in Cuba, and online access is restricted, with numerous media outlets being blocked. Included in the inaccessible sites is his blog, which publishes criticisms of the racism in Cuba. Thanks to social media sites such as Facebook, Rodríguez can stay up-to-date with the racial tensions in Cuba. And from his home in Spain, he is able to publish Cubans’ experiences online.

Various organizations exist in Cuba that aim to educate about African traditions, said Lazaro G. Guevara Lopez, a Cuban writer. But they do not necessarily tell the most authentic history of blacks on the island, he said.

So Guevara and Rodríguez have started multiple groups, such as the Foundation African American of Cuba, promoting equality in the country. They are only given that freedom, however, because they now live in Barcelona, Spain.

Rodríguez said it costs about $5 to use the Internet for an hour in Cuba, and online access is restricted, with numerous media outlets being blocked. Included in the inaccessible sites is his blog, which publishes criticisms of the racism in Cuba. Thanks to social media sites such as Facebook, Rodríguez can stay up-to-date with the racial tensions in Cuba. And from his home in Spain, he is able to publish Cubans’ experiences online.

“It is easy for an immigrant to communicate with someone in the country,” Rodríguez said. It just requires using indirect means, such as emailing his blog posts to people, as opposed to them reading it on the site.

Rodríguez said that despite racial tensions in Cuba, “the mix (of ethnicities) is normal.”

But so is the racism, he added.

Zabala recalled a time when he saw a black 15-year-old running from a white teenager who was throwing rocks at him in the streets of Havana. The 30-year-old orthopedic surgeon, who worked at the hospital Calixto Garcia de la Habana, said similar incidents are common.

Calzon said inequality is felt more subtly as well.

“If your skin is very, very black, your chances of getting a job at a front desk or something at a hotel, your chances are very limited,” Calzon said.

When asked about his own ethnicity, Calzon was quick to answer.

“To be a Cuban is to be an Afro-Cuban,” he said. “We eat the black beans the slaves brought from Africa.”